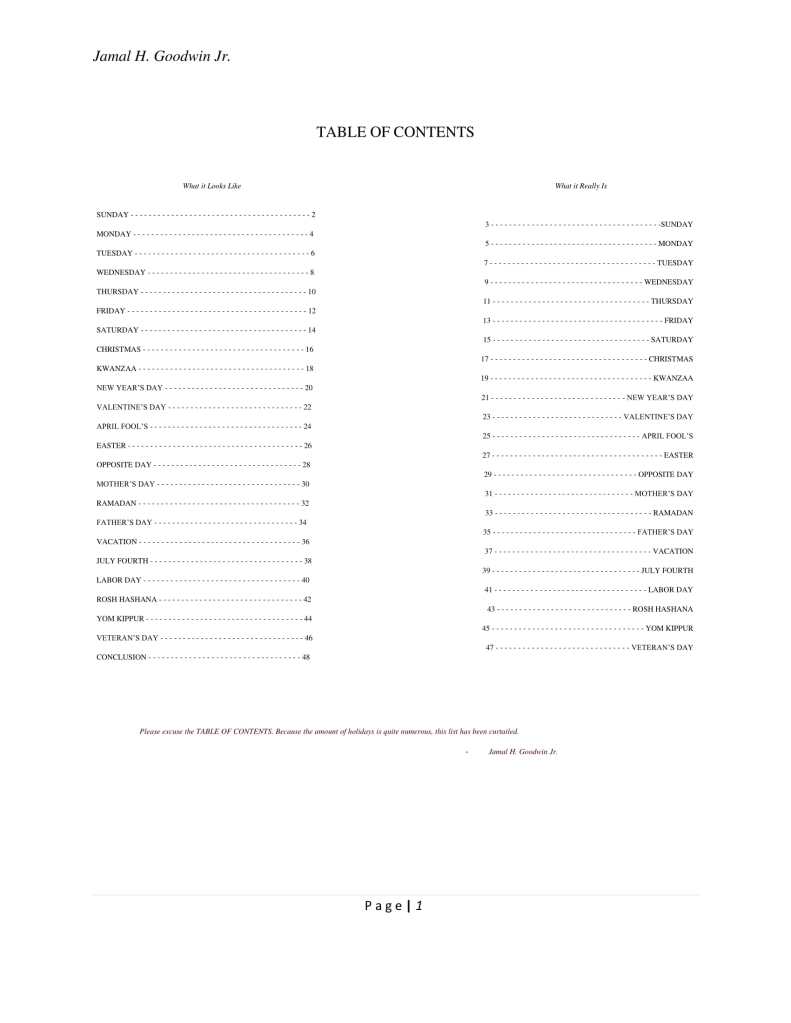

Origin of This Piece:

Modifying prose isn’t the only way to create noteworthy fiction. Yes, plain style with its mostly simple sentences differs heavily from grand style, which is used in speeches, or purple prose, which imitates poetry. The format of a story, be it traditional or something unique, like a letter (epistolary fiction), effects the reading experience just as much if not more than syntax.

In my fall 2020 semester, I wrote a story in my usual middle-sometimes-purple style, but tried something new and used the format of reference fiction. It mimics an encyclopedia.

The title of this story comes from one of my favorite books: Chemistry by Weike Wang. On page 52, she uses the line, “Still we fight beside clothing racks.” It’s a metaphor for a couple; they are arguing but not seeing one another. The fight is obscured. Intentions are misunderstood.

What it Looks Like

SUNDAY

Before she can even reach the kitchen, she is reached to by the hand of the memories. Stubby. Recent and innocent, like a baby, like the one she will bear in some months. The three of them were talking an hour ago: her, her husband, and the little one, stirring inside her. Her husband had insisted on doing the dishes, saying she should rest after cleaning all Saturday. She had been eating a sandwich and laughed between bites. He joked that with all the baby clothes she had bought, she was too ready to be a mother, and she said he’d become a helicopter dad before he knew it.

She is returning to the kitchen to munch on some Oreos. She deserves to treat herself. She walks on the carpet she vacuumed smooth yesterday and walks past the couch she dusted. But when she enters the dining room, her husband calls out to her from the bedroom. He asks, politely, can she iron his dress shirt? She smiles. He’s just woken from a nap, and she remembers that he’s got an important brunch at work tomorrow. She assures him his clothes will be ready, and she fetches his best shirt to iron for him.

P a g e | 2

What it Really Is

SUNDAY

She walks atop the clutter at this point. Her head is in that daze again, responsibilities flickering by like stills from film tape, responsibilities flickering by and she can latch on to none of them, she’s stressed again, she can feel another one coming on: a panic attack. Her breaths hasten because the crumbs she vacuumed off the carpet yesterday and the clothes pile she had folded this morning have reverted back to their sickly forms. In an environment like this, where urine reeks from behind the toilet and kitchen grease clings to the walls in the living room, where she is the only one who acknowledges habits need to be changed, how can she raise a baby?

She slumps against the kitchen wall, desperate for something to ease her mind. She whips her head to the right. All that remains in the cupboard: a nearly empty box of Oreos. She palms a few.

But before she can chew them, her husband shouts, Can you iron somethin’ for me? I’ve got a brunch with the guys at work tomorrow.

P a g e | 3

MONDAY

“I was checking the inboxes, like she asked me to. Then she went around and told Charles I abandoned his assignment. When she’s the co-supervisor. What kinda nonsense—!”

And as she talked, Rosie saw the sadness creep on Daniel’s face. Deep wrinkles eked along his aged forehead; maggots, she called them when she was mad. But she wasn’t mad, no. Not in this moment. She was yelling but she, too, was sad, and Daniel, seeing this sadness, grew mad, mad with a rage that glowed from his squinted eyes, but he didn’t burst, he wouldn’t explode, he just nodded, awaiting a chance to speak, to assuage his ailing wife, knowing that helping her is better than vengeance towards her coworker.

“That girl is twenty years than me. She should show some respect. Don’t you agree dear?”

And she could tell that her words had torn Daniel. He never liked to see her so worked up, but he knew he had to give her space to express herself.

And so he agreed.

P a g e | 4

MONDAY

And as Rosemarie talked, Daniel’s frustration nearly boiled over. He didn’t process a word of her ranting. Instead, he perused her weaknesses. How many times had he pleaded with her to just get another job? He had lost count. Paul and Aaron fled as soon as they reached adulthood; they didn’t visit unless they were certain she was using a vacation day. From a young age they learned to pity their mother. If it wasn’t because she was overloaded with spreadsheets, it was the coworkers nitpicking behind her back. The common denominator? Sitting in a cubicle surrounded by a bunch of jerks.

He didn’t feel the tight folding of skin on his forehead, but the growing tears stung his eyes. Rosemarie dug her elbows into her thighs, gripping her chin between her palms. She was shouting something or other. She would lose that songlike voice of hers, the one that elicited the smile of passersby. So often, strangers would greet her like a dear friend.

Why not apply to be a flight attendant? You would make a great stewardess. Or you could go back and get your degree, become a physical therapist. Daniel had made many pleas to her over the years. She had just waved them off. By choice or by accident, Rosemarie had been groomed to key excel sheets and do customer service.

A “Don’t you agree dear?” broke his train of thought.

With a dense sigh, he nodded.

P a g e | 5

SATURDAY

Date night! But we’re not like other couples. Hubby and me watch bad movies. It’s so fun! Last time, we watched The Last Airbender. Cute kid, but his arrow wasn’t even blue. And they called him “Ahngh,” like a weird grunt or something.

Tonight we watched Independence Day: Resurgence. Boy was that crappy! The blonde scientist guy, getting probed by the floating robotic ball. What were those writers thinking? I think I waited the whole movie to see Will Smith, but all we got was his discount son, looked nothing like the real dude.

P a g e | 14

SATURDAY

We were supposed to host a movie night with friends. And… the idea was to watch something that we both would like… But of course that never happens. He always talks over me and we ended up watching the worst movie of the 2010s. He’s got this penchant for shitty movies, it irks me to no end. I couldn’t just come out and tell people that though, tell them he made all the decisions in the relationship. So “why not,” I said, and said I wanted to watch it, and told the gang watching bad movies was something we always did. I think my act was pretty convincing, though everyone left before the climax. I was stuck watching the rest with him. They ate all the popcorn, he devoured the nachos and salsa, and there were no hoagies left to eat. We sat on that couch til the last credits line scrolled by, at 2:13 AM.

P a g e | 15

CHRISTMAS

We sit at an orange and beige checkered table, the light from stained glass descending behind us. Glossy and pink, the marble floor glows.

I knew Jasmine wasn’t in the mood for Chinese, and she falls into depressions during the Christmas season, so I stepped up and brought her here: El Vino de Reyes.

We pick up our menus. A plastic flap covers the text; surrounding the items are clumps of crimson dust fixed into shapes, like flowers and stars.

Each waiter who passes us nods and says, Cómo estáis? Finally, we can feel not broke! Jasmine loves it… I know she does. The way she beams at me as I fork bits of salad; the mirth with which she stirs her quinoa; the knife’s ding on her plate as she cuts slices of flan.

Her grimace had faded, and she stopped looking out at the holiday lights and snowy Christmas tree across the street. This was our time.

P a g e | 16

CHRISTMAS

I love Jasmine, and I know she’s an atheist, but she couldn’t be bothered to spend this night with me and my parents. I tried to hide my disappointment. She was too elated to pay attention. We both love Spanish food, so El Vino de Reyes was the perfect place to cheer her up. Pricey, but “Chipotle doesn’t cut it,” she had frequently reminded me.

The holiday season thrusts her into depressions. Usually, her jokes brought light to my day, but when she’s like this I must be the one who does the shoulder carrying.

Maybe this is a good thing. My parents never understood Jasmine’s eccentricities. They’re still baffled I married an atheist. “You can’t choose who you fall in love with,” I told them.

Every so often, she looks up from her sugary quinoa. Her smile is radiant. I try to enjoy my paella, but I can’t help but think of the agony my wallet’s going to suffer once the bill arrives.

P a g e | 17